No Shore Thing: Why There’s Concern For Piping Plovers

Beach season is approaching, and so are the piping plovers.

With the return of warm weather in the northeast comes the seasonal return of piping plovers — those tiny shorebirds who build nests on the beaches of Long Island and much of the Atlantic coast this time of year.

The latest cause for concern for the federally protected species is Hurricane Matthew, which hit the Bahamas last fall — the prime season for piping plovers to winter there. Scientists say it’s too soon to know how the population was affected but they’ll be keeping a cautious eye out for their return north this year.

As they do, here’s what you need to know about the piping plover, its habits on Long Island, and why the tiny bird may affect your beach access.

Snow birds

For many years researchers knew that piping plovers migrated south to Florida, the Gulf Coast and Texas for the winter. But 11 years ago, international census efforts began and have revealed the tiny birds also fly internationally to places like the Bahamas, Cuba and Turks and Caicos. About one-quarter of the Atlantic Coast population winters in the Bahamas, primarily on the northern part of Andros Island, Joulter Cays and the Berry Islands.

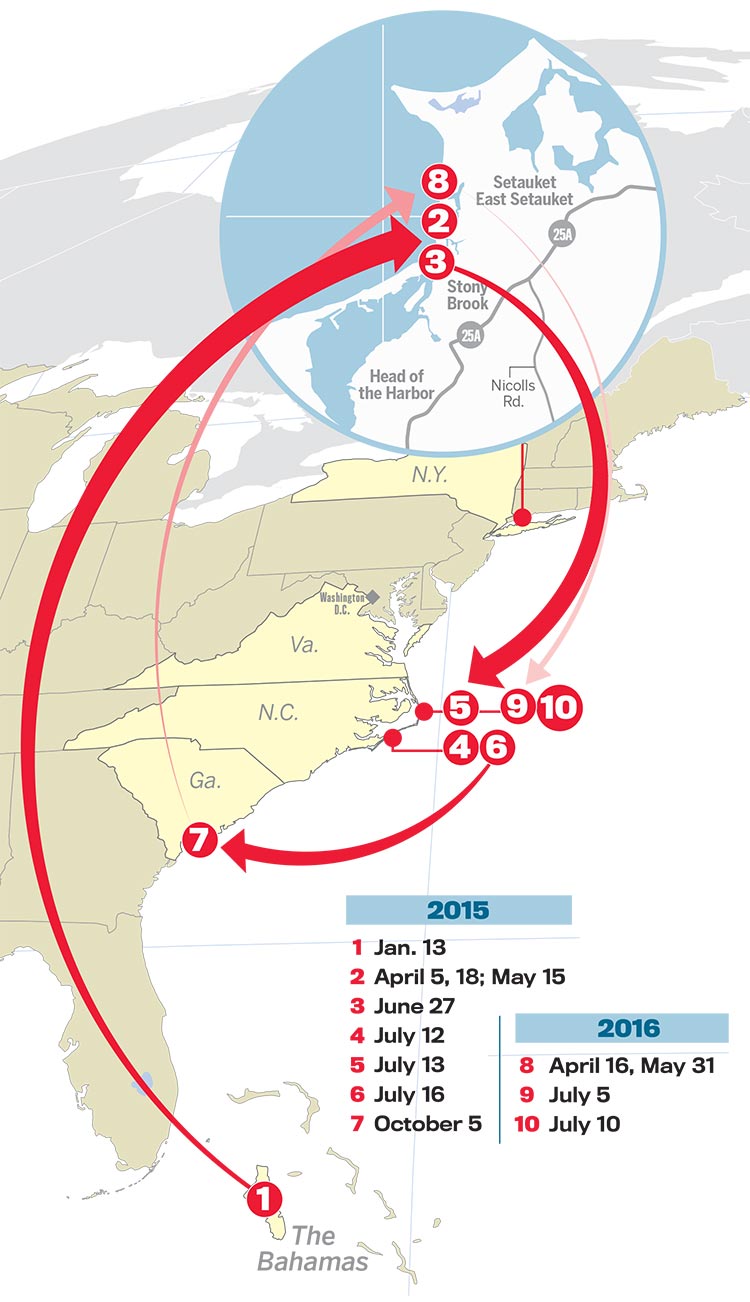

The path of one piping plover shows its movement through the Bahamas, Georgia, North Carolina, and Long Island. Credit: Newsday / Rod Eyer

Battle for the beach

The birds begin arriving on Long Island in mid-March and start courting. The male sets up shallow scrapes – they aren’t nests until there are eggs – above the high tide mark in typically wide-open sandy spots. The female will pick the most appealing scrape, usually an indentation in the sand with shells and rocks, no grasses. Eggs are laid between May and June. Incubation takes up to 31 days and the young fledge within about 35 days. By September, most are gone.

By the numbers

Only half of all plovers survive their first year. The birds, part of the Atlantic Coast population, are listed as endangered in the state and have been protected under the federal Endangered Species Act since 1986. Less than 4,000 can be found along the eastern Atlantic, from South Carolina to Canada. In 2016, 381 breeding pairs came to New York, the bulk of them on Long Island. The biggest population is at Jones Beach State Park.

Keep out

These tine shorebirds weigh between 1.5 and 2.25 ounces and are about 5.5 inches long. Their first clutch usually consists of four eggs. If the nest is not successful, the plovers will continue to try a few more times but each clutch will typically have one less egg. So, the more the birds are left alone and the more successful the nesting, the faster they will leave — and the sooner protective fencing, signs and restrictions on recreation will end.