The Grumman emblem is emblazoned on a tank atop Plant 5 in Bethpage in March 1966. Photo credit: Newsday / Dick Kraus

For a time, Grumman Aerospace seemed as if it put all of Long Island to work.

It began manufacturing in Bethpage, on grounds that would swell to 600 acres, in 1937. The U.S. Navy opened its 105-acre Naval Weapons Industrial Reserve Plant, operated by Grumman, soon after.

“Grummanites” — including the women who’d be dubbed “The Janes Who Made the Planes” — produced the thousands of Hellcat fighters that helped the United States destroy enemy aircraft over the Pacific in World War II.

At its peak, more than 20,000 people would be a part of the company’s thrumming, 24/7 operation. It became known for its massive company picnics and youth sports sponsorships (the esteemed Panthers football club was named after a famed Grumman jet).

But beneath the surface, a problem was developing.

The first warnings that activities at Grumman threatened the environment came not long after the war. They would continue consistently through the late 1980s, when Grumman, as it would say in 2018, “sought to understand how legacy military operations, that were standard practices during America’s history, may have contaminated soil and groundwater.”

The warnings actually trickled out for decades before that in often-confidential government and company reports, which are now coming to light for the first time as a result of a nine-month Newsday investigation.

In the most prophetic, the Nassau County Health Department in 1955 concluded that toxic discharges from Grumman “might eventually contaminate the water in public supply wells at a considerable distance.”

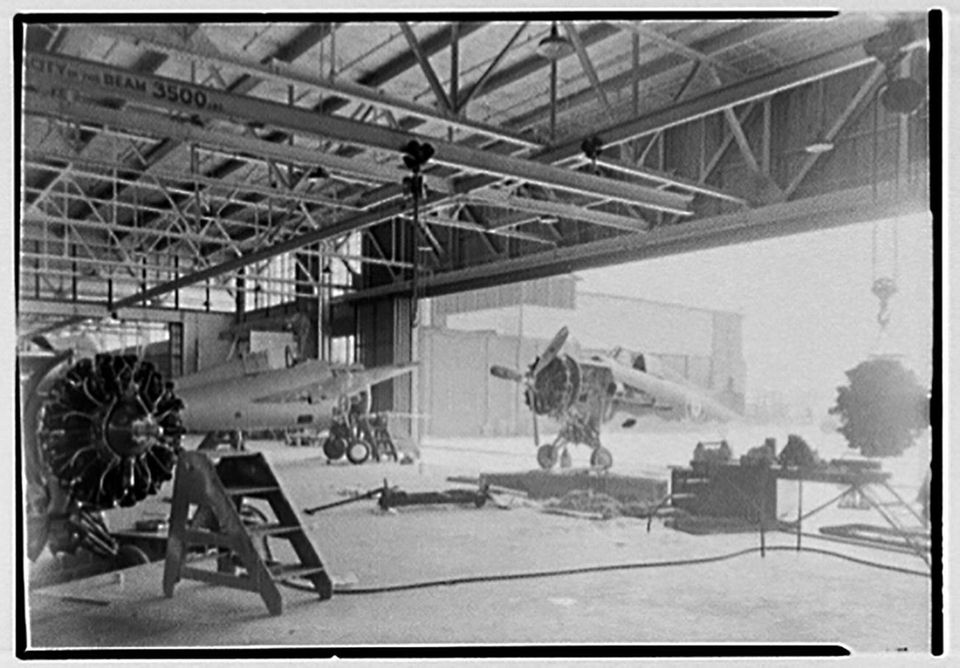

Planes under construction in October 1940 at Grumman’s Bethpage facility. Photo credit: Library of Congress

Today the still-spreading plume of groundwater contaminants is 4.3 miles long, 2.1 miles wide and at points 900 feet deep. It extends through much of Bethpage and has required treatment of public water supplies serving numerous other communities.

The county’s caution 65 years ago, as well as ones that began intensifying in the mid-1970s, were largely met with denials from a company with great political sway and an underlying deference from government at all levels.

At first, heavy metals were the primary contaminants of concern. But they’d soon be eclipsed by the degreasing solvent trichloroethylene, or TCE, which Grumman used and disposed of in abundant volumes that seeped into groundwater.

As a result, the organic compound, a carcinogen, is now the most voluminous of two dozen contaminants within the plume.

Northrop Grumman, as the company has been known since a rival defense contractor acquired it in 1994, shares cleanup responsibility with the Navy, which owned a sixth of the land where Grumman operated its plant.

There’s a pretty standard playbook that these companies apply.

Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of Center for International Environmental Law

Both parties point to substantial work they’ve done under oversight by the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Superfund program for hazardous waste sites.

Most significantly, the Navy has paid tens of millions of dollars for public water supply treatment, while Northrop Grumman has since the late 1990s operated an extensive system that extracts the toxic chemicals from beneath its original properties to stop further spread.

“The company’s ongoing evaluation shows it is effectively capturing groundwater contaminants as it was designed to do,” Northrop Grumman said in a 2018 fact sheet about the Bethpage pollution.

Yet enormous amounts of contaminants have already spread from the old company grounds, even as Northrop Grumman has long disputed the severity of the pollution. It continues to oppose the most-comprehensive off-site plume containment plans and has fought millions of dollars in cleanup costs that fell to taxpayers.

One environmental lawyer who has taken on timber, plastics and oil companies said the company appears to be using an oft-employed corporate template for forestalling financial and reputational damage.

“There’s a pretty standard playbook that these companies apply,” said Carroll Muffett, president and CEO for the nonprofit advocacy group Center for International Environmental Law.

“First, they deny that anything is happening, and then they deny that what is happening is a problem,” he said. “Then they deny that they’re responsible, and then at the end, when all of those other things have been disproven, they argue that it’s not economically viable to fix the problem.”

Frequently, Northrop Grumman has pointed out that at the time Grumman employed its historical waste disposal practices, they were legal, a factor that does not lessen its obligation under the Superfund law.

The company declined multiple requests for interviews but stated in the fact sheet that it has worked for more than 20 years with state, local and federal officials “to investigate and remediate legacy environmental conditions.” It noted it has signed three formal state cleanup decisions and “is implementing its obligations under these agreements.”

“Northrop Grumman has devoted significant resources to our environmental efforts in Bethpage and spent over $200 million to date to help clean up the environment and protect the health and well-being of the community,” company spokesman Vic Beck said in a further statement to Newsday.

Early warnings

The first known instance of Grumman contaminants infiltrating Bethpage’s public water supply came nearly 75 years ago.

In 1947, the state notified Grumman that the Central Park Water District (the Bethpage Water District’s predecessor) found chromium in one of its public supply wells. Grumman sprayed the metal plating agent on its aircraft parts. The resulting wastewaters containing the toxic substance were dried into sludges and, as was common at the time, disposed of directly into the ground.

Even with far less understanding of the health hazards of industrial chemicals, Grumman was accused of endangering Long Island’s sole source aquifer for drinking water.

Then-Rep. W. Kingsland Macy told Newsday he “feared the waters that carried metallic poisons into the ground may eventually contaminate the water table.”

The company responded in Newsday that it “doubted” the plant’s operations put the public at risk. The chromium levels in the water, some of which remain, were then hundreds of times above today’s acceptable standards. The metal also is still present in soil on Grumman’s old properties.

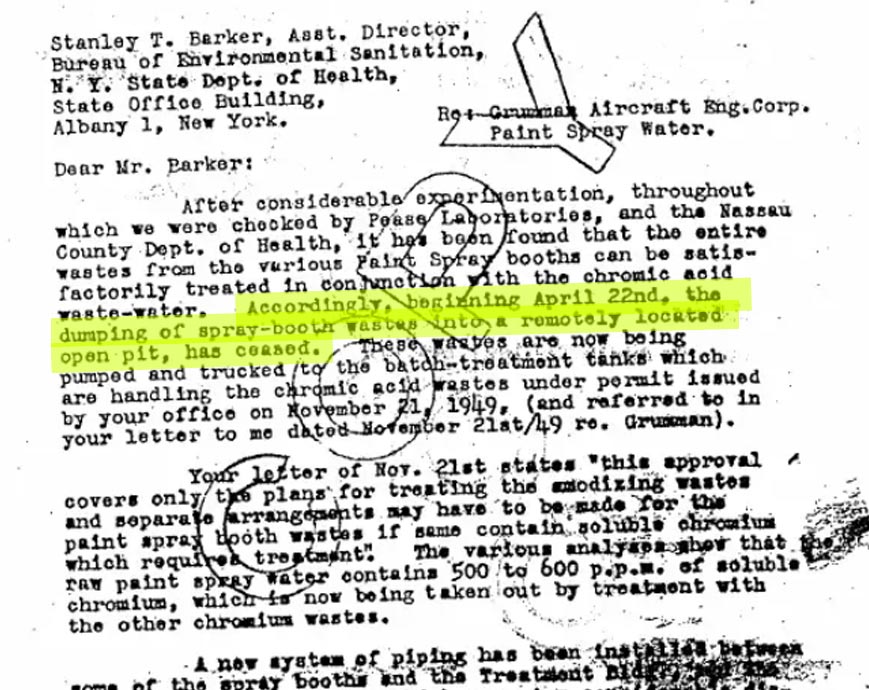

By late 1949, Grumman agreed to pay for new water district wells and said it had changed its disposal practices to address the contamination. Referring to how it would now treat its wastewaters at an on-site facility, the company wrote to the state health department in early 1950 that “the dumping of spray-booth wastes into a remotely located open pit, has ceased,” according to a letter filed in a 2012 federal lawsuit by Grumman’s former insurers, the Travelers Cos.

“Accordingly, beginning April 22nd, the dumping of spray-booth wastes into a remotely located open pit, has ceased.”

1950 letter from Grumman to state health official See full letterTravelers successfully argued that it has no duty to defend the company against liabilities for past practices in part because Grumman hadn’t provided it with enough notice about its role in or knowledge of environmental pollution.

The letter was one of several marked confidential in the case but mistakenly left unsealed.

Even after the 1950 letter, Grumman continued to dispose of the treated sludge — as well as other wastes — throughout its facility, where it had dug at least a dozen shallow artificial ponds, or recharge basins.

Regulators at the time were beginning to key into the groundwater dangers of chromium and several common industrial metals, including arsenic and cadmium, the latter of which would also show up in Grumman’s sludges.

Another chemical, however, ended up being of graver consequence.

In one internal document, Grumman says it began using TCE in 1949. The chlorinated solvent, a degreasing agent, was sprayed from wands and soaked into rags that would wipe down work areas. But its most-common application was through massive vats that boiled the solvent into vapors to remove impurities from metal parts.

“These degreasers were everywhere, especially in the aircraft industry,” said Steve Swisdak, a forensic historian who reconstructs manufacturing practices, with a focus on TCE use, that have led to modern environmental contamination. “It was remarkably efficient at cleaning metal parts.”

Military manuals from the 1940s warned of the dangers of TCE, counseling against inhalation and skin contact and, in one general caution, advising that it not be dumped into sewage systems. But for all the apprehension, it would be decades until the solvent’s dangers to groundwater became known.

A defender of Grumman’s legacy said the company can’t be judged too harshly.

“We were much less concerned with the environment in those days. And the net result is we were sloppy,” said George Hochbrueckner, a former congressman from Suffolk County who worked at Grumman facilities in the 1960s and early ’70s. “But at the time, the level of environmental protection wasn’t there as it is today. So it’s a problem we created ourselves when we were in good times doing good things for the nation.”

George Hochbrueckner worked at Grumman in the 1960s and early ’70s before representing Long Island in the U.S. House, where he was nicknamed “the Grumman congressman.” He is shown here at an event in June 2017. Photo credit: Randee Daddona

‘Such wastes do not dilute’

Still, contemporary records reveal more than one early warning to Grumman that its general practices could harm the environment.

In 1955, Grumman applied to the state for two new industrial production wells as it expanded an operation that would pump tens of millions of gallons of water per week to its plants.

That set up the prophetic warning from the Nassau County Health Department predicting that the pollution could spread. The department objected to the application, noting in a letter — another left unsealed in the Travelers lawsuit — that the company’s recharge basins “contain toxic chemicals in sufficient quantities to pollute the ground water supply in the area to concentrations well beyond maximum allowable limits for a satisfactory drinking water supply.”

At the time, the U.S. Public Health Service had already recommended levels of chromium in drinking water not exceed 50 parts per billion.

The county letter states that chromium (as well as cadmium, another carcinogen) at levels of up to 1,700 parts per billion remained in Grumman’s basins. The company said then that it believed its treatments were effective, though state regulators later surmised otherwise.

“To allow the applicant to draw further ground water from additional wells in the area without adequate protection of the supply would be to permit the contamination of that much more water beyond the vital drinking water standards which must be maintained in Nassau County at all costs,” the health department wrote.

Responding to the application, the state said the county’s objections didn’t warrant denying approval for the new wells but pointedly found that the objections were valid and should prompt investigation and corrective action.

The decision, also left unsealed in the insurance case, is noteworthy as well for including the earliest known concern — 65 years ago — that groundwater pollution on the site would expand in the aquifer below and migrate laterally and vertically.

Nassau’s investigations, the state reported, “indicate that such wastes do not dilute in the ground water as had previously been believed, but that the wastes concentrate as slugs or ribbons which might eventually contaminate the water in public supply wells at a considerable distance.”

But the concerns were not publicized, and Grumman continued to enjoy residents’ esteem.

Its reputation was bolstered further when in 1962 it donated 18 acres to the Town of Oyster Bay for construction of Bethpage Community Park. There was no public mention that a part of the site contained the “remotely located open pit” used as a dumpsite. It took 40 years for that to emerge.

Newsday covered the land donation in 1962. Photo credit: Newsday archives

“Back then, anyone who said a bad word about Grumman was risking a punch in the mouth,” Bruce Tuttle, a test pilot who worked for the company for nearly four decades, told Newsday in 1997.

A county public health engineer caught the spirit of the day in a 1966 summary he wrote to Grumman of on-site wastewater sampling: “As the expression goes, ‘You must be doing something right.’ Keep up the good work.”

‘I could even smell it’

At the end of the 1960s, there were multiple signs Grumman would soon face an environmental storm.

California in 1966 enacted one of the nation’s strictest air pollution laws, banning the use of numerous chemicals employed heavily by its aerospace industry, including TCE. Two years later, the state’s lawmakers specifically beat back an industry effort to exempt the solvent.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency was formed in 1970 and the Clean Water Act passed in 1972. By the mid-1970s, other states had passed laws limiting industrial TCE use.

In April 1975, the National Cancer Institute reported that TCE was causing organ cancers in mice. That October, the federal Labor Department proposed limiting nationwide worker exposure to TCE after growing concern that its inhalation could damage the kidneys, heart, liver and central nervous system, and cause cancer.

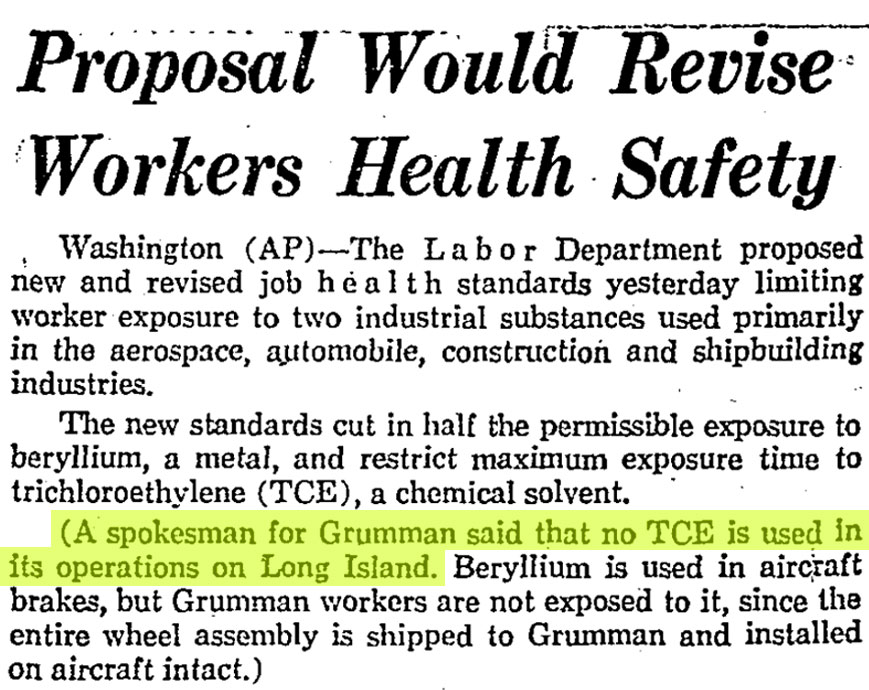

An Oct. 15, 1975, story in Newsday about the Labor Department announcement included this line: “A spokesman for Grumman said that no TCE is used in its operations on Long Island.”

In fact, its use of TCE was evident. Not only had Grumman utilized TCE for more than 25 years, but by this point it relied on it so heavily — through the vapor degreasers and large liquid spray wands — that it was stored in a 4,000-gallon aboveground tank at one of its plants and placed into drums for recycling.

Grumman had long dried wastewaters containing TCE in its basins. It had dumped the rags soaked with the solvent into pits, including the one that became part of the 18-acre park. All of this had already led to groundwater contamination.

“A spokesman for Grumman said that no TCE is used in its operations on Long Island.”

Newsday, Oct. 15, 1975 See full article

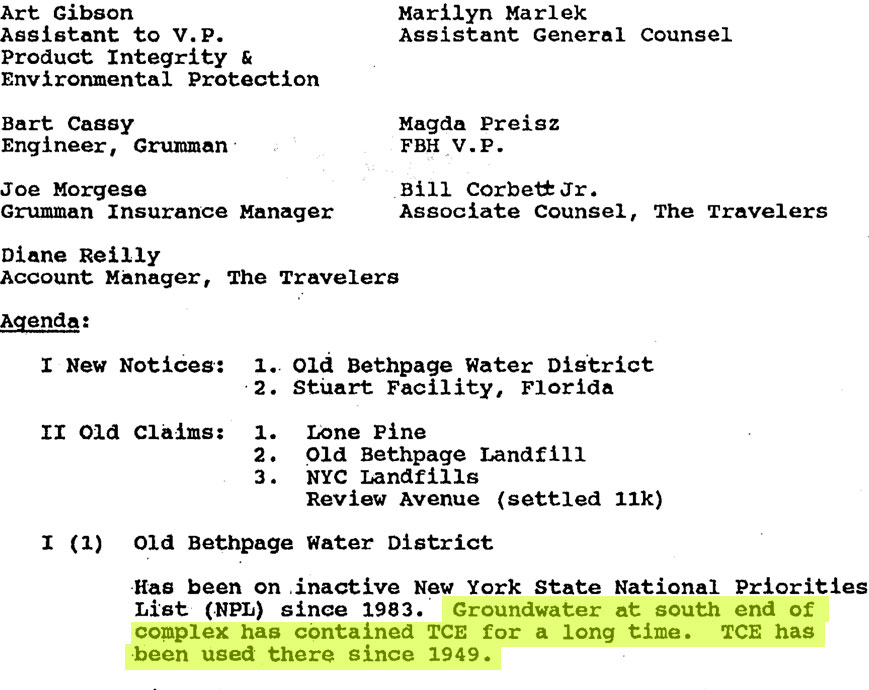

“Groundwater at south end of complex has contained TCE for a long time. TCE has been used there since 1949.”

1989 memo summarizing internal meeting between Grumman and its insurer See full documentPortions of one plant “were dumping grounds for many exotic metals and unidentified liquid substances,” Brian C. Hickey, a Bethpage resident who worked at the company from 1973 to 1981, observed in 1998.

Hickey, who became a New York City fire captain and died in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, further noted, in a public comment on an early cleanup plan, “Grumman, like many other manufacturers, dumped, spilled or mismanaged the control of numerous hazardous materials into the ground.”

He added, “We have lived on the border of a 40-year chemical leak.”

Another “Grummanite” would confirm this in explicit terms.

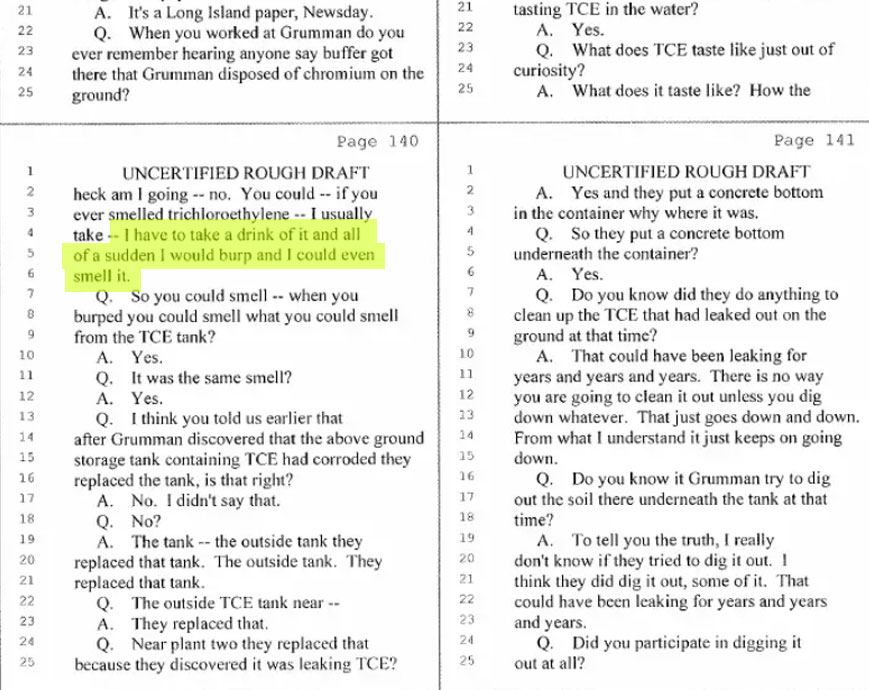

William Kovarik worked for Grumman for more than 40 years, including at the plant where TCE was stored. He said in a deposition conducted for the insurance lawsuit that the carcinogen had likely leaked from a rotted-out tank bottom into the ground for “years and years and years” in the 1970s before being discovered.

“By the time it got down to the water table, who knows?” he said in 2013, referring to TCE’s ability to permeate the soil and pollute the aquifer before detection. “It really goes down fast.”

Kovarik, a lifelong Bohemia resident who died in 2019 at 82, described the TCE tank as two stories high and 15 feet wide. He said Grumman knew then of worker complaints about its unexplained TCE losses.

At the time the solvent dripped, contaminant removal systems had not been placed on any water supply wells — including those used for drinking — within or beyond the facility.

“I would burp and I could even smell it,” Kovarik said.

“I … take a drink of it and all of a sudden I would burp and I could even smell it.”

2013 federal court deposition of a former Grumman employee See full documentCounty begins probe

In late 1973, the Nassau County Health Department began looking into taste and odor complaints that Grumman had received from workers about its private drinking water supply. The county’s two-year investigation was conducted with no public disclosure.

The report it issued at the conclusion stands out for two reasons.

It presented strong evidence of severe TCE contamination at Grumman. Yet its wording and framing worked to minimize those findings while targeting another company, the neighboring Hooker Chemical Co., which would later gain notoriety as the cause of the pollution at Love Canal in upstate New York.

Hicksville-based Hooker was undoubtedly guilty of damaging the environment: It had dumped vinyl chloride, another carcinogen, that made its way into Grumman wells. Grumman did not use vinyl chloride, which produces polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, for pipes, wire coatings and packing materials. It was flagged as a potential carcinogen in 1974, months before TCE.

But the county’s final report overlooked Grumman’s responsibility for the bulk of the pollution. Striking are subtle changes of wording from a preliminary version of the report dated May 1975 and the final version issued that November.

In the preliminary version, the county concluded that: “the discharge of sanitary and industrial wastes at and in the vicinity of the Grumman Corporation is considered responsible for the degradation in quality of the Grumman Corporation wells.”

But in the final version, the words “at and” are missing from the phrase “at and in the vicinity of the Grumman Corporation.” In the same sentence, Hooker is the only named offender:

“The discharge of sanitary wastes in the vicinity of the Grumman Corporation and the discharge of industrial wastes, particularly those previously discharged by the Hooker Chemical Corporation, is considered responsible for the degradation in quality of Grumman Corporation wells.”

While the [county report] immediately noted the severity of the overall situation, it blamed Grumman for none of it.

Test results of two additional Grumman wells and Hooker’s wastewater supply — first reported in October 1975 — underscore how lopsided this conclusion was.

They showed 50 parts per billion of vinyl chloride in one Grumman well and none in the other. Hooker’s wastewater also had 50 parts per billion of vinyl chloride. While the state had yet to establish a maximum drinking water level for such organic chemicals, in 1977 it would: 10 parts per billion for vinyl chloride and 50 for TCE.

The sample of Hooker’s wastewater contained 80 parts per billion of TCE.

But in one of the Grumman wells it was 500, 100 times today’s limit.

The results — which came out the same month Grumman told Newsday that it did not use TCE — raised strong questions about whether Grumman, rather than Hooker, was the primary source of TCE contamination. Groundwater contamination is typically strongest at its source.

‘I was stunned’

When Nassau issued its final summary, the TCE results were submerged on the next-to-last page. While the document immediately noted the severity of the overall situation, calling it “a most serious instance of … contamination,” it blamed Grumman for none of it. Hooker was named on the first page.

Decades later, two Northrop Grumman employees involved in the company’s cleanup were shocked by the extent of the TCE contamination on Grumman’s grounds, which by this point had been long established as a product of the company’s operations.

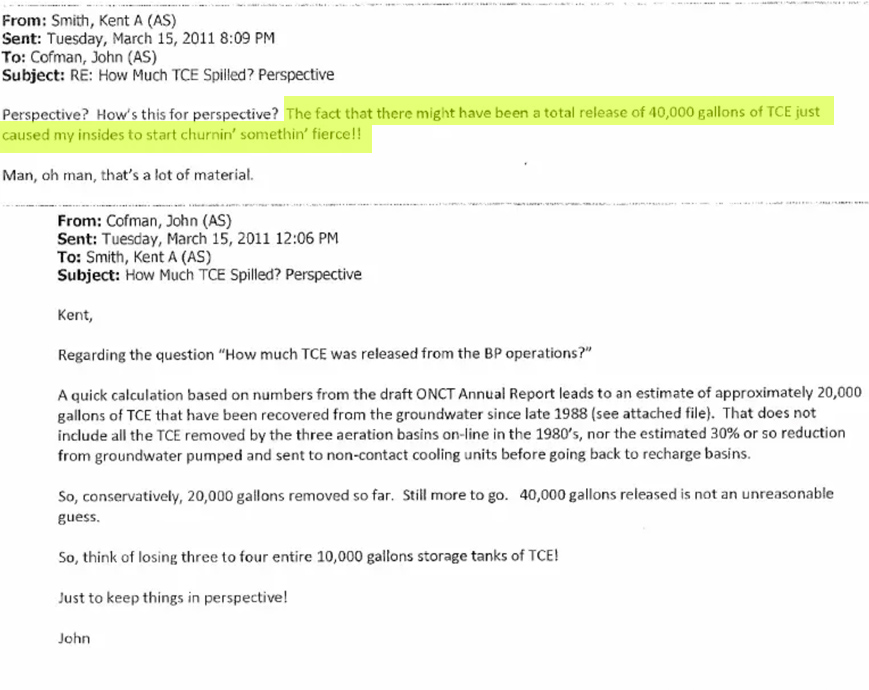

In a 2011 email, John Cofman, a senior environmental engineer, estimated that 20,000 gallons, or more than 200,000 pounds, of TCE had been removed from groundwater beneath Grumman’s original 600 acres through on-site cleanup systems. He noted that there could be another 20,000 gallons to go.

“So, think of losing three to four entire 10,000 gallons storage tanks of TCE!” Cofman wrote in the email, another left unsealed in the federal insurance lawsuit. “Just to keep things in perspective!”

“Perspective? How’s this for perspective?” replied the recipient of the email, Kent A. Smith, an environmental, safety, health and medical manager. “The fact that there might have been a total release of 40,000 gallons of TCE just caused my insides to start churnin’ somethin’ fierce!! Man, oh man, that’s a lot of material.”

Cofman replied: “Yes — I was stunned when looking at this.”

“The fact that there might have been a total release of 40,000 gallons of TCE just caused my insides to start churnin’ somethin’ fierce!!”

2011 email between two Northrop Grumman employees See full emailBut when the contamination at Grumman finally reached the public in 1976, few people registered such alarm over the TCE levels.

As state and county regulators largely blamed Hooker, they downplayed the severity of the overall problem. Grumman denied it had any role.

Meanwhile, the plume grew unabated.