Inside the FBI’s Long Island Gang Task Force

It’s the command center for the federal task force leading Long Island’s fight against street gangs, most notably MS-13, the criminal organization accused of dozens of vicious killings in Suffolk and Nassau.

Geraldine Hart, the 21-year FBI veteran who leads the FBI’s Long Island Gang Task Force, said when it comes to MS-13 the bureau’s chief target is the 200 hard-core members of the gang at large on Long Island. But the task force also focuses on other violent street gangs operating on the Island, such as the Bloods, Crips and Latin Kings.

“We deal with the worst of the worst,” said Hart, who also is the chief FBI supervisor on the Island. The task force focuses on made — or, as they are known within MS-13, “jumped in” — members of the gang, not “kids [who] can make gang signs,” she said.

We deal with the worst of the worst.FBI Senior Supervisory Special Agent Geraldine Hart. Photo by J. Conrad Williams Jr.

President Donald Trump, who has linked gang violence with illegal immigration, visited Brentwood in July and spoke about needing to “liberate” towns on Long Island from the scourge of the gang. In April, Attorney General Jeff Sessions came to Long Island and pledged “to demolish” MS-13.

Sources say there have been at one time or another at least 11 different MS-13 chapters active on Long Island. Most of its members hail from El Salvador and other Central American countries.

And there is new information that MS-13’s leadership in El Salvador is now once again attempting to centralize its control over all the Long Island chapters, the sources said.

Inside the Melville offices there are 33 investigators and crime analysts who make up the task force — equally divided between FBI agents and crime analysts and their counterparts in 10 other law enforcement organizations, including Nassau and Suffolk county police.

Hart, bureau officials and agents, including Michael McGarrity, the head of the FBI’s overall criminal division for the New York area, agreed to talk about the work of the gang task force in general terms. They declined to talk about current cases or investigations, such as the recent arrest of the MS-13 members in the killings of the two Brentwood teenage girls or four young men in Central Islip.

Since 2010, there have been charges filed against defendants in 40 gang-related homicides in Suffolk and Nassau as a result of the work of the task force, according to FBI figures. And of the 17 MS-13-related homicides in Suffolk since 2016, nine of them so far were solved by task force investigators, the FBI says.

Since its establishment in 2003, the task force has made 1,190 arrests, including 280 members of MS-13, of whom 30 were top leaders of chapters, according to FBI statistics. Most arrests have resulted in successful prosecutions on charges including murder, attempted murder and assault in federal court in Central Islip. Prosecutors in the office of Acting Eastern District U.S. Attorney Bridget Rohde work closely with the task force in developing cases, officials say.

The task force also gets regular input from other investigators not stationed at the Melville office, and other police departments on Long Island that could help them identify a pattern — such as the arrest of a suspected gang member at a particular location — that might lead to other arrests or a better understanding of an MS-13 chapter or hierarchy.

McGarrity and Hart say that the task force uses the same “enterprise theory” in dealing with gangs that the FBI has used on traditional organized crime: Each chapter is a single organization or enterprise, all of whose members are involved and which should be completely eliminated, member by member.

Big progress being made in ridding our country of MS-13 gang members and gang members in general. MAKE AMERICA SAFE AGAIN!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 27, 2017

Hart is more than familiar with the enterprise theory; she led the FBI’s New York squads investigating the Genovese, Bonnano and Colombo organized crime families.

Working in collaboration with local police and others that may have gang information but not the resources or the time to deal with gang activity, the FBI can bring its greater resources to bear on all the members of a chapter, McGarrity said.

Those resources include a network of FBI agents in other MS-13 hot spots such as the Washington, D.C. suburbs, Boston, and Los Angeles, as well as about a half-dozen FBI agents permanently stationed in El Salvador working with Salvadorean law enforcement officials on the gang and sharing information with the task force on Long Island.

Further bolstering the work of the task force are federal criminal laws such as Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) that provides for more penalties and allow prosecutors to charge criminal elements with a broader range of crimes.

“The latest surge in MS-13 criminal activity is being met head-on and has resulted in significant racketeering charges, due in large part to the collective experience our office and task force members have developed,” Rohde said.

And the FBI has deep financial resources allowing for significant payments for informants, as well as for overtime pay for local law enforcement officers.

A key element in the gang fight is the ability to place cooperators in the federal witness protection program.

For example, in the case of the MS-13 members who in 2010 murdered 2-year-old Diego Torres and his mother, Vanessa Argueta — because she showed disrespect to the gang — a key informant and gang associate, Carla Santos, was placed in the witness program. She testified in 2013 in federal court against one of the killers and was guarded by federal marshals from the program, according to court records. The defendant was convicted of murder and other charges and was sentenced to life in prison plus 35.

And another of the killers convicted in the case, Argueta’s former boyfriend, Juan Garcia, was captured in 2014 in Central America, a day after he was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list and a $100,000 reward was offered for his arrest.

But McGarrity and Hart stressed that the unstinting cooperation between the FBI and the local Long Island police forces and other agencies is vital to the task force’s work.

Raid breaks up meeting

Soon after its establishment in 2003, the task force had a big win. At dusk on Oct. 10, 2004, as an FBI surveillance plane circled overhead, 50 heavily armed agents stormed a three-story building at 25 Montague Place in Brooklyn, hurling six flash-bang grenades to break up a planned secret meeting of the heads and other members of the Long Island chapters of the MS-13 street gang called by the leadership in El Salvador.

An infrared film of the event recorded from the plane shows gang members tossing guns out windows and unsuccessfully attempting to evade capture by fleeing from the building’s roof to adjoining rooftops. In all, 16 members of the gang, were arrested without incident at the building and in follow-up raids in the following days. The raid resulted in convictions in several murders as well as other violent crimes, according to officials and court records.

The raid also resulted in quashing — to this day — the effort by the gang’s central leadership in El Salvador to coordinate the activities of its Long Island chapters, say sources familiar with the results of the raid.

Three of those arrested had been in direct contact with the leadership in El Salvador, which ordered the LI chapters to unite and follow the Central American leadership, the sources said. A more centralized, Central-American-based control of MS-13’s cliques in an area is more typical of the gang structure in Los Angeles, the Washington suburbs, and the Boston area, the sources said.

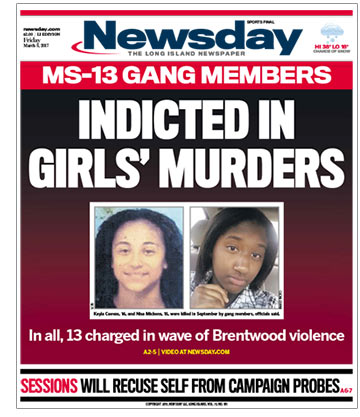

Most recently the task force’s work in the face of the latest surge in violence by MS-13 has resulted in the arrests of gang members accused in: the killings of two teenage girls who attended Brentwood High School and the slayings of four young men in a Central Islip park.

In March, six months after the September killings of the Brentwood teenage girls — Kayla Cuevas, 16, and Nisa Mickens, 15 — the task force’s work resulted in the arrests of a half-dozen members of MS-13 in the slayings. Gang members believed Cuevas had disrespected them, while Mickens had been assaulted while walking down a street with her friend, officials said. More than a half-dozen members of the MS-13 street gang “whose primary mission is murder” were indicted in the killings, officials said.

In July, four months after the April slayings in a Central Islip park of four young men, the task force arrested and charged about a dozen defendants the in the slayings of Justin Llivicura, 16, of East Patchogue; Jorge Tigre, 18, of Bellport; Michael Lopez Banegas, 20, of Brentwood; and Jefferson Villalobos, 18, of Pompano Beach, Florida, who was on Long Island visiting his cousin Banegas at the time, officials have said. MS-13 members believe some of the four had disrespected the gang and were believed to be members of a rival gang, authorities have said.

Specific skills are key

While many investigators on the task might be involved in providing information on a case, a four-member team — two FBI agents and two other investigators — is typically responsible for investigating one particular case, Hart says.

The FBI supervisor in the task force’s early days, Robert Hart — no relation to Geraldine Hart — who is now an assistant Nassau County Police Commissioner, said the FBI selected for the task force agents who speak Spanish, have the ability to get along with people with a special sensitivity, and those with an understanding of the Salvadorean culture and MS-13 structure and habits.

It was not unusual, for example, for an agent to help getting a suspect to cooperate by buying a suspect pupusas, the corn tortilla filled with cheese or beans or pork that is a staple of El Salvadorean cuisine, according to a source.

Also helping drive the work of the task force is what investigators see as the unrestrained brutality of MS-13.

FBI agent Ed Heslin, a Spanish-speaking former immigration lawyer, said that even after serving as an investigator with the bureau in Afghanistan, “I was shocked” by the close-up violence of MS-13 members on Long Island.

In Afghanistan, the killing was at a distance: “Not personal” involving “somebody with an IED,” Heslin said.

But to the MS-13, “It’s close up and personal,” where victims are attacked face-to-face with machetes and knives and bats.

Hart found it “shocking to me” that the gang would murder a 2-year-old. As someone who was raised on Long Island, Hart said she finds it “very satisfying … to have some input in diminishing these gangs.”

Hart says that there is “an ebb and flow” to MS-13’s notoriety and visible presence on Long Island. The task force would typically arrest and prosecutors convict the major MS-13 members on Long Island, but several years later the gang’s cliques would resurface with newer members from Central America.

Experts who study MS-13 say this ebb and flow reflects both downturns in El Salvador economy, making the United State an attractive place for people to seek work, as well as the waxing and waning of the violent wars between criminal gangs and the military and police in El Salvador.

Ron Hosko, former assistant director of the FBI’s criminal division, and now head of the Law Enforcement Criminal Defense Fund, said law enforcement alone cannot permanently stamp out MS-13; they will persist until the financial and immigration issues involving El Salvador are solved.

But whatever the overall solution, Hart says, when it comes to stopping MS-13 violence and arresting those who commit the gang’s brutal crimes.: “We don’t go away … We are never going to stop. We always have and will always be doing cases.”