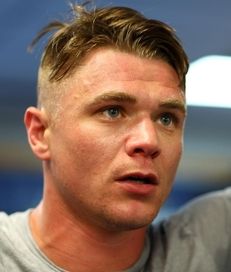

Gian Villante discussed two very different sets of hiccups ahead of his fight at the UFC’s Long Island debut on Saturday.

First up, those irritating ones he was unable to shake in the days leading into his last two fights.

The second set, however, belonged to the New York State Athletic Commission, which is in its first year regulating mixed martial arts.

“It’s difficult, they do some things differently, but they’re new at this, so you can’t blame them for having their hiccups in the beginning,” Villante said. “They’re going to have their hiccups in the beginning and stuff like that but they’re still early on.”

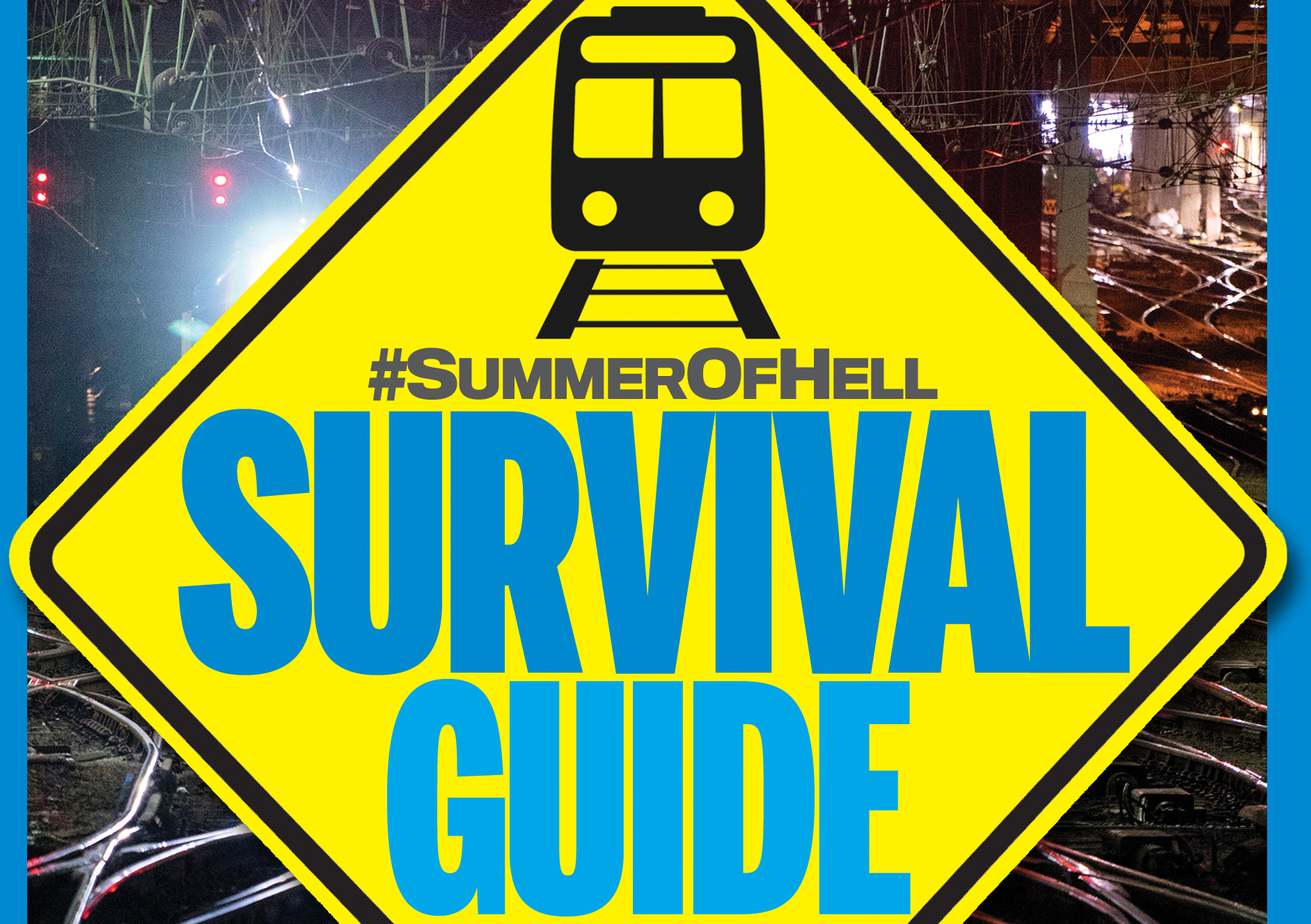

NYSAC has made its share of mistakes in these initial months, most notably Daniel Cormier’s towel on the scale trick and the confusion over replay, referees and what’s a legal strike in the Chris Weidman vs. Gegard Mousasi fight. But, with each event, things seem to be improving.

New York became the final place in North America to remove its ban on MMA when the State Assembly passed the bill in March 2016. A month later, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo signed the bill at a Madison Square Garden ceremony. In November, the UFC hosted its first New York show at MSG, setting attendance and live gate records for the venue and promotion.

NYSAC has overseen no less than seven major professional MMA events in total, and UFC on Fox 25 last Saturday at Nassau Coliseum went off without incident. It was the fifth trip to New York for the UFC, and regardless of previous missteps, the promotion has no qualms about continuing to bring events here.

“Yeah, there’s little things with the commission, whether we just need to coordinate it all, but each show has gotten easier and easier and they’re running fine,” said Marc Ratner, UFC vice president of regulatory affairs. “I’m very, very pleased with it.”

In the beginning

As weigh-ins and medical checks for the UFC’s first show on Long Island wrapped up Friday morning, Ratner sounded comfortable with how the state has embraced the sport in the first year.

“There was a pent-up awareness and people wanted to see it,” said Ratner, who led the charge for MMA legalization. “It took us eight years to get OKd here. We can tell from the television ratings, the number of pay-per-view buys, this is a great area for us to promote in. When we finally got here, we had the biggest show we’ve ever had here.”

In an email ahead of Saturday’s event, NYSAC spokesman Laz Benitez said the response to legal MMA in the state has been positive.

“Fighters want to fight in New York, the world’s biggest stage,” Benitez wrote. “As for promoters and fans, the State has already hosted six at-or-near capacity cards, so the demand is there and the reaction has been tremendous.”

As positive as the numbers and responses have been, all sides acknowledge the unique challenge of building a new operation.

“The biggest inherent challenge was indeed just that, starting a new product from scratch, although our experience with boxing was helpful,” Benitez said. “The Commission began from the ground floor to develop a game plan that would be fully executable once the sport was legalized.” Ratner believes any issues are part of a learning curve and that even the little things take time to pick up.

“First of all, we’re doing an early morning weigh-in, this is different,” Ratner said. “We’ve got to see if they’re going to use a digital scale, if they’re going to use what we call a meat scale. Doctors, how long’s it going to take to do every medical. Little small things, nothing extraordinary.”

UFC 205 at Madison Square Garden broke promotional and arena gate records as Conor McGregor won his second UFC title against Eddie Alvarez in the main event. That card on Nov. 12, 2016, was monumental for many reasons. But it also highlighted issues a new set of regulators can face.

“Fighter safety and the integrity of combative sports in New York State are our top priorities,” Benitez said. “And after exhaustive work, preparation and consultation with a multitude of industry experts, the commission put together a framework in time for the sport’s debut last November at Madison Square Garden that achieved those goals.”

The commission’s work resulted in a set of regulations unique to the state, causing some confusion at the start. Under New York’s rules, fighters who don’t make weight still must be within a certain range for the fight to be held. This rule was partially responsible for the cancellation of a bout between Kelvin Gastelum and Donald Cerrone last November. It also forced Jim Miller to come in above 156 pounds for his lightweight bout after opponent Thiago Alves missed the limit by more than six pounds.

When the UFC visited Albany last December, Ratner said a miscommunication left the fighters without a doctor on site who could perform stitches, a typical fixture at UFC events.

“We pride ourselves in having one of the doctors stitch and in Albany, we couldn’t get a doctor to stitch there, we had to have [fighters] wait in the hospital,” Ratner said. “It’s a big convenience for the fighters to not have to wait in the hospital. We always ask for one New York licensed doctor who can stitch. We pay for all that stuff, there was just a miscommunication and we couldn’t get the person there on time.”

Following February’s UFC 208 at Barclays Center, Holly Holm filed and lost an appeal after referee Todd Anderson did not penalize Germaine de Randamie for strikes Holm deemed to be thrown after the round ended. There also was scrutiny of the judging in de Randamie’s win, as well as Anderson Silva’s win over Derek Brunson.

But at UFC 210 in Buffalo last April, the miscues reached their pinnacle. The event nearly lost a fighter over the state’s rule banning female boxers with breast implants from competing. NYSAC reviewed Pearl Gonzalez’s medical records and cleared her to fight that afternoon.

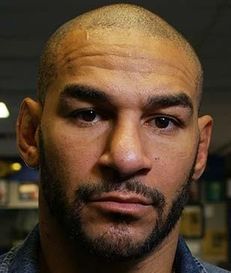

More notably, it was the site of Cormier’s infamous towel grab. After first weighing in at 206.2 pounds — over the 205-pound limit for a light heavyweight championship fight — Cormier weighed in again a couple minutes later. That is allowed under NYSAC guidelines for a championship fight, but not a non-title fight, a fact expressly stated in a boxing guidelines memorandum but not spelled out in the state’s MMA guidelines posted on their website.

A couple minutes later, Cormier put his hands on the towel covering his naked body from view while weighing in for the second time. He was 205 pounds.

“We learned that if you’re going to have a towel around a fighter to make sure that he doesn’t have his hands on it,” Ratner said. “That may have happened before, but this was pretty crazy that it did happen. And sadly, it was tough on the commission.”

In a meeting five days after UFC 210, NYSAC amended language in its guidelines to state a fighter “shall not make physical contact with any person or object other than the scale.”

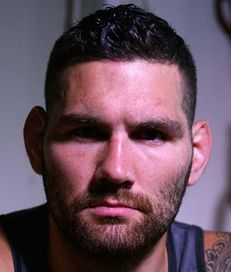

UFC 210 also put Long Island’s Weidman at the center of controversy. Weidman’s fight was paused after he took two knees to the head from Mousasi originally deemed illegal by referee Dan Miragliotta. But after the use of video review, the strikes were deemed legal and Weidman was ruled unable to continue by doctors. Weidman was handed a TKO loss.

Weidman and others were under the impression replay wasn’t allowed in New York, but it wasn’t strictly banned. NYSAC officials later said the use of replay was justified.

“There was a question of did they have replay or don’t they have replay in the Weidman fight,” Ratner said. “The commission told me they didn’t, then they said they did afterwards.”

Weidman appealed the decision, which was denied in the weeks ahead of UFC Long Island.

Benitez did not comment on specific incidents, but said the NYSAC is learning from each event it oversees.

“As with every new venture and opportunity, there have certainly been instances that the commission has learned and grown from,” Benitez said. “The commission also tapped into an existing pool of established referees, judges and inspectors with MMA experience, making the transition more seamless.”

Improving with time

NYSAC took a publicity hit for these incidents, but there have been some notable improvements, especially at weigh-ins. At Bellator NYC’s weigh-ins in June, Sergio Da Silva repeatedly tried to shift his balance and fool the scale to come in on weight. Three different NYSAC officials told Da Silva to stop the antics, step off the scale and start again.

The commission also was quick to stop Eryk Anders from touching the towel during his weigh-in for UFC Long Island last week.

For the most part, fighters appear understanding of the learning curve.

Villante, who fought in Albany last December, thinks the commission would be smart to seek guidance from New Jersey, the first state to adopt unified rules for the sport back in 2001.

“If they can learn a little bit from (New Jersey State Athletic and Control Board counsel) Nick Lembo over in Jersey, I think that’s one of the finest-run commissions. If they can learn a little bit from those guys, maybe, the next state over, I think that’d be a great thing,” Villante said. “But they’re learning on the fly, which is tough to do, but they’re getting it and I think, in time, it’ll get better and better.”

Benitez said NYSAC consulted numerous commissions in drafting their plan and remains in contact with other states as well as the Association of Boxing Commissions.

Patrick Cummins fought in New York for the second time on Saturday, defeating Villante by split decision. The Pennsylvania native was on the Buffalo card but had no issues getting ready to fight.

“I felt good with the commission. I know there were a lot of problems, especially during that Buffalo card,” Cummins said. “But, me? It didn’t affect me much, so, I don’t know. I don’t know whether to be thankful or to say that, yeah New York’s doing a great job.”

Darren Elkins, who defeated Dennis Bermudez in Saturday’s co-main event, said he understands what New York is going through after fighting in the early days of legal MMA near his hometown.

“I’m back in the day when there was no commission where I came from in Indiana, Chicago and that area. When we first got the commission, they had a lot of snags and they had a lot of things going on, too,” Elkins said. “It’s just working out the kinks, that’s what they’ve gotta do. When they figure that out, it’ll go all smooth. We’re so used to these commissions that have been around for a long time that we’re just not used to seeing something this new.”

The insurance issue

Still, the newness of it all has caused some fighters to pause. New Jersey’s Jim Miller fought in New York twice. Those will be his last fights here, he said.

“I think they’re just trying to reinvent the wheel,” Miller told BJPenn.com Radio in April. “It’s not that they’re doing things that are unsafe or anything like that. They’re trying to take really good care of the fighters. But they’re kind of being really overbearing with it, and a lot of these rules you don’t hear about.”

NYSAC requires additional neurological and blood examinations ahead of fights compared with other commissions such as New Jersey.

Ratner doesn’t see anything wrong with adding new protections, but he does hope to see commissions come up with a universal rule set to help ease confusion here and elsewhere.

“One of the problems, whether it be boxing or MMA, and I’ve been advocating this for 25 years or more, we don’t have standardized medical testing or standardized rules in every state,” Ratner said. “Now we don’t even have unified fight rules, but standardized medicals are extremely important. And I’m a states-rights guy, but we should be able to have the same blood tests, licensure, same hepatitis, HIV, same kind of stuff about MRIs, license calendar year. And every state is a little bit different, and there’s no reason for that.”

Ratner also noted that each show NYSAC oversees is high-visibility due to a $1 million life-threatening traumatic brain injury insurance requirement set by the state legislature, leaving few learning opportunities on smaller stages.

“They don’t have small fights. Every fight is a big fight, whether it’s us or it’s boxing,” Ratner said. “I know that the commission is working on the rules now to make it better insurance-wise. Whether they can do that or not, I don’t know. But what you want is small fights, too, to work on things.”

Benitez said the commission is continually assessing all policies and procedures, but any change to the insurance requirement would need to be approved and passed by the state legislature.

“This is unique coverage in the combative sports world,” Benitez said.

Fight on

New York may be among the strictest states, but Ratner has not yet heard of fighters turning down fights here.

“I’ve had fighters tell me they don’t want to fight in certain places like in Mexico because of the altitude or something like that, but no, it’s fine here,” Ratner said.

Benitez said the state also is not aware of any licensees shying from New York because of medical guidelines.

For some fighters, thinking about where they compete goes against their fighting mentality.

“I never think twice about taking a fight. As soon as something’s offered, I take it, that’s my style,” Cummins said. “I feel like just because it’s so new to New York, it’s going to be tough, but I’m hoping they have things figured out now. No towel blunders this time around.” Elkins said he leaves it to the people who sign his check to make those decisions.

“Honestly, I’ve seen some of the things that are going on there, but all you can do is move forward,” Elkins said. “When they ask you to fight somewhere, it’s work, man. It’s either that you work or you don’t work, and I like to work and I like to compete. So, I took it. Is there concern? A little bit, but hopefully I keep things in my own hands and I don’t have to worry about anything.”

Bermudez believes fighters who do things the right way should have nothing to worry about.

“Everything I do, I just show up and do me,” Bermudez said. “I’m not a panicky, worrying kind of guy,” Bermudez said. “I don’t cheat the system in any way, shape or form so I have nothing to be concerned with.”

Gastelum was back in New York for a main event after his weight issues and NYSAC rules forced him off UFC 205 at the Garden.

“There was a little bit of hesitation, but at the same time, this was an amazing opportunity that I couldn’t pass up,” Gastelum said.

Even Weidman, Long Island’s biggest star who defeated Gastelum in Saturday’s main event, had people close to him telling him to avoid fighting in his home state. But, fighting at Nassau Coliseum was too much to pass up.

“Definitely a little hesitation, more hesitation with, like, my team, the people around me who care about me, they don’t like the way the New York commission dealt with a lot of stuff,” Weidman said. “Behind the scenes, with me, with the way the fight went down, with that and other things. There were some people that were like, ‘You’re not fighting, I don’t care, you’re not fighting in New York.’

“And I just did it.”